When a client walks into Eve Townsend’s office for therapy, they’re often carrying a snack, drink, or new prescription.

That’s because Townsend, a licensed clinical social worker, provides mental healthcare in a CVS store. Stationed in a nondescript consultation room very much unlike the therapist offices you might recognize from cable television dramas, Townsend’s job is to help anyone who asks for support.

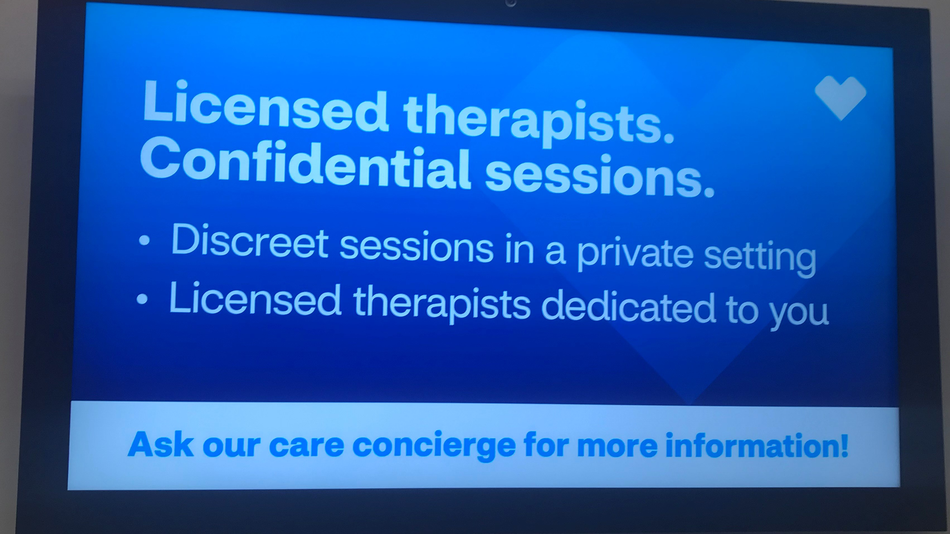

The CVS pharmacist might recommend a customer to Townsend after screening them for depression and asking if they want assistance. A client might discover Townsend through CVS brochures and mailers, or by word-of-mouth. Sometimes customers walk into the store to get milk or bread, see signs asking if they’d like to talk to someone about how they’re feeling, and decide to take CVS up on the unexpected offer.

What they tell Townsend these days goes something like this: They’re stressed, anxious, and often feeling depressed.

“I think a lot of that, I’m quite sure, is related to the COVID-19 pandemic, political discourse, civil unrest, and just individuals actually realizing that what they’re going through is a little more beyond what they’re capable of handling,” says Townsend, who works in a CVS in suburban Philadelphia.

Townsend started her job in late January as part of a pilot to test placing licensed clinical social workers in select CVS stores in Philadelphia, Houston, and Tampa. The company has also posted listings for social workers in places like Phoenix, Brooklyn, Seattle, and Omaha. Therapists are part of the chain’s MinuteClinics within their HealthHUBs, which provide a range of health and wellness products and services, including access to a nurse practitioner or physician assistant for treatment of urgent and chronic conditions. The mental health concept is an attempt to solve two major problems.

In-store signs let CVS customers know therapy is available.

Image: COURTESY OF CVS

As a major retailer in the space and owner of the insurance company Aetna, CVS knows that healthcare costs in the U.S. are high. Its own internal data, along with research, suggest that when people receive treatment and care for both their physical and mental health needs, it leads to less spending over time. It makes sense when considering, for example, the patient with diabetes who takes medication to control their blood sugar but whose depression goes untreated. If that depression means they don’t exercise or eat well, a prescription can only do so much.

Yet CVS also sees alarming gaps in the country’s mental healthcare services. There’s a shortage of providers. Many don’t take insurance. Wait lists are long. These and other realities make it difficult or impossible for someone to get care when they want it. The aim is to simplify access to mental health treatment, removing from the equation the confusion and complexity of locating a qualified mental health provider. CVS is trying to meet people where they are: in the cereal aisle, picking out nail polish, getting a flu shot, or grabbing a medication refill.

What you won’t find, at least on Townsend’s watch, is a “cookie cutter” approach to therapy. Townsend, a longtime social worker, practices what she calls “social work 101.”

“We are advocates for change.”

“We are advocates for change,” she says, referring to her professional training. This means hearing what a client needs to be holistically well and trouble-shooting how to get those resources. That can include providing social services referrals for someone who is food or housing insecure. Townsend directs people who need psychiatric care or substance misuse treatment to outside providers and support groups. In partnership with the nurse practitioner and pharmacist, she might triage suggestions for someone with multiple health conditions.

The skill set that someone like Townsend possesses is why CVS chose to hire licensed social workers who have a masters degree in the field. Cara McNulty, president of Aetna Behavioral Health and EAP (Employee Assistance Program), says the goal is to bring on therapists from the local community, who know it well and can connect with clients.

“Their interpersonal skills really, really matter, because you get one chance to have that first impression with that person who has reached for help, to make them feel welcome, normalize the situation, reassure them that it’s OK, especially reassuring them that it’s OK to not be OK,” says McNulty.

She’s also aware that an empathetic approach will likely appeal to CVS customers wary of seeking mental healthcare because of stigma or past negative experiences. CVS’ strategy may be particularly attractive to millennials and Gen Z customers, many of whom may be less worried about stigma and more concerned that a CVS therapist will be more interested in diagnosing them than empathetically listening to them.

Theresa Nguyen, chief program officer and vice president of research and innovation of the advocacy organization Mental Health America, said putting social workers in a non-clinical setting like a CVS store, compared to a doctor’s office or hospital, could be transformational. In effect, CVS is reminding people they can get help, that services are available, or catching them at a time when they might “otherwise fall through the cracks,” said Nguyen. (CVS has partnered with MHA to discuss improving mental healthcare access at pharmacies, but was not involved in the development of the pilot.)

Nguyen, a licensed social worker who has frequently worked with people experiencing mental health conditions and poverty, said that she often worried about her clients whose symptoms might flair up when they went to fill their prescriptions or get food. If she knew which corner store or pharmacy they frequented, she might feel more confident in their safety.

“If I know people there are friendly and kind, I know this is a safe space for my client to get support,” she said. When that wasn’t the case, “I would always get worried it’s going to get elevated to a 911 call.”

“If I know people there are friendly and kind, I know this is a safe space for my client to get support.”

Now that Nguyen works on policy issues, she hears from pharmacy staff that they see customers in distress but don’t have the skills or time to help. To Nguyen, making highly-skilled social workers available in a pharmacy can prevent crises for both the customers and employees. She also hopes that it reduces the barriers that keep many people from seeking help and normalizes having a conversation about mental health. If seeing treatment happen in an ordinary place demystifies what it means to talk to a therapist, perhaps more CVS customers will consider pursuing it.

Customers typically come to Townsend after seeing in-store messaging or receiving a referral from the pharmacy. Like other social workers in the same job, she’ll perform an initial assessment and listen to what a customer needs, including food, shelter, or assistance with an abusive relationship. Next she’ll try to problem-solve the urgent issues, then schedule a future appointment or refer the customer to another mental health provider, if necessary. CVS accepts insurance and Medicaid for Townsend’s services, which may cover all or part of the appointment fee. If someone is uninsured, Townsend will see if the customer qualifies for local mental healthcare coverage through county or state resources. Customers can also pay out-of-pocket. The cost varies depending on insurance coverage.

Townsend says there’s no predetermined end date to therapy with her. Clients can come and go as they need. Recently she treated an anxious 15-year-old who came in with his parent. They discussed the “cognitive distortions,” or negative thought patterns, that kept surfacing in his mind and ways to reframe those thoughts. He returned two weeks later saying he felt better, but he can keep seeing Townsend if he chooses.

“It has given me the opportunity to see diverse populations of people — young ones, older ones — who are seeking support,” says Townsend of her new job. “And [for customers] to be able to access the help that they need in a facility or in a forum like this, where you can receive all of these other additional services, is great. It works.”

If you need to talk to someone about your mental health, Crisis Text Line provides free, confidential support 24/7. Text CRISIS to 741741 to be connected to a crisis counselor. Contact the NAMI HelpLine at 1-800-950-NAMI, Monday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. – 8:00 p.m. ET, or email info@nami.org.