Should all go as planned, NASA’s car-sized Perseverance rover will plummet through the Martian atmosphere in February 2021, reaching speeds of over 13,000 mph. After landing, NASA engineers will instruct the rover to raise its tall mast, on top of which, among some critical exploration instruments, is a microphone.

The rover’s launch is now imminent, as the window for blasting into space opens up on July 30. Upon arriving at Mars, the robot’s primary mission is to scour the Jezero Crater (an ancient lakebed) for signs of past microbial life, while also gathering soil and rocks for a later mission to shuttle back to Earth. And as the rover rumbles over Mars’ terrain, it will record eerie, extraterrestrial sounds — a true rarity in space exploration.

“We think we’ll hear Earth-like sounds on a planet that’s tens of millions of miles away,” said Bruce Betts, a planetary scientist at The Planetary Society, an organization that promotes the exploration of space.

The rover’s 15-millimeter microphone is expected to pick up the whoosh of the Martian wind, and the likes of swirling dust devils, should they cross paths with Perseverance. The microphone will also record the sound of the rover zapping Martian rocks with a laser, to detect the make-up of the rocks from some 25 feet away. This laser zapping, in fact, is why NASA approved the microphone at all. The microphone atop Perseverance wasn’t truly a romantic exploit to hear Mars.

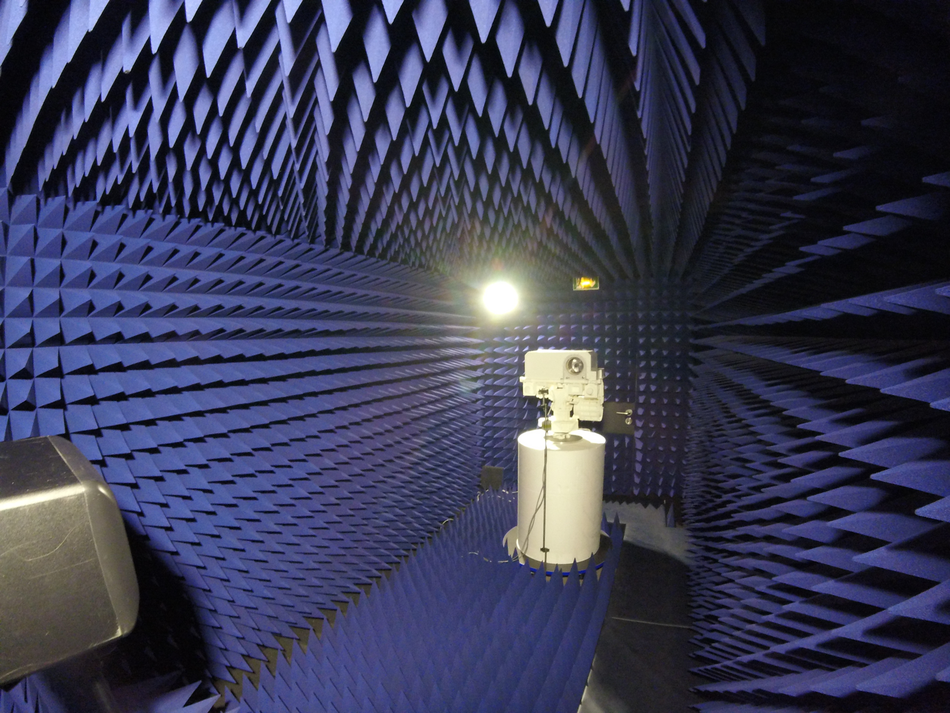

Microphone testing on the Perseverance rover’s SuperCam in a sound-isolating chamber.

Image: isae-supaero

The microphone on the rover’s SuperCam is circled in red.

Image: irap

Space aboard the rover is limited and valuable, so NASA required the microphone (or most anything on Perseverance) to have a scientific purpose, explained Roger Wiens, a planetary scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory who leads the SuperCam (SuperCam is the laser-shooting instrument atop the rover where the microphone is attached). Wiens team, however, discovered a scientific purpose for a microphone: When the laser shoots a softer rock it leaves a little pit, which makes a different popping sound than a laser zap on harder rocks. This sound is a way to identify rocks, giving NASA better information about the most promising places to visit in the expansive Martian desert.

“We can determine the hardness of a rock, and that’s without even driving up to it,” said Wiens, who noted that knowing a rock’s hardness leads to insights about what it’s made of.

Yet, with this approved scientific purpose now comes a new way to sense Mars, beyond the visually grand pictures of Martian valleys, hills, and sunsets beamed back to Earth over the last couple of decades. The rover will record sound for three and a half minutes at a time.

“We can see things on Mars,” said Wiens. “We’d like to hear things on Mars.”

“We’d like to hear things on Mars.”

But anything recorded on Mars will sound differently than the same noise would on Earth. That’s because the Martian atmosphere is much thinner than Earth’s, and it’s also composed largely of a different gas, carbon dioxide (Earth’s atmosphere is mostly nitrogen and oxygen). A thinner atmosphere means sound has less of a medium to pass through (space and the Moon, places with no atmosphere, are soundless). So Martian sounds will be quieter and won’t travel nearly as far as those on Earth. A scream on Earth traveling over a kilometer would journey only some 16 yards on Mars.

“It’s just a different place,” said Betts.

The thin Martian air will alter the sound’s pitch, too. “The sound speed is slow on Mars,” explained Wiens, which results in lower pitches. On Mars, a higher-pitched zap or pop (that we expect to hear on Earth) will sound more like the lower tones of the toms on a drum-set, he said.

Perseverance won’t be the first time humanity has endeavored to record Martian sounds. But it could be the first to succeed. “We’ve been trying to get microphones on Mars for more than 20 years,” said Betts.

The Mars Polar Lander, equipped with a microphone funded by The Planetary Society, crashed into the Martian desert in 1999. Due to an electronics problem, NASA never activated the microphone on the Phoenix Lander, which settled on Mars in 2008.

A conceptual graphic of the Perseverance Rover on Mars.

Image: nasa

Humanity has captured snippets of sound before on other worlds — just not many. In 1981, the Soviet Union’s Venera 13 and 14 probes recorded a staticky light wind on Venus, before the planet’s crushing atmosphere and pizza oven-like heat destroyed the landers. They lasted just 127 minutes and 57 minutes, respectively. “Venus is a pretty hostile place,” noted Bill Barry, NASA’s chief historian. Nearly a quarter of a century later, in 2005, the Huygens probe successfully parachuted through the thick atmosphere of Saturn’s enthralling moon, Titan. A microphone captured the noisy sound of its descent.

“It’s a sample of what a traveler riding with Huygens would have heard during the descent,” wrote NASA.

A microphone on the side of the Perseverance rover will record the rover dropping through the atmosphere, too, which means the mission has two microphones.

It’s the microphone atop Perseverance, however, that will record Martian sound as the rover explores the Jezero Crater, where some 3.5 billion years ago rivers drained inside, creating a lake — and, perhaps, a home for primitive life.

Microphones aren’t usually a priority in the exploration of other worlds. “Microphones have been at the bottom of the list,” said NASA’s Barry. But now, a microphone’s getting a real shot.