July brought us the best close-up photos of the sun that the world has ever seen. Now, there are some new ones.

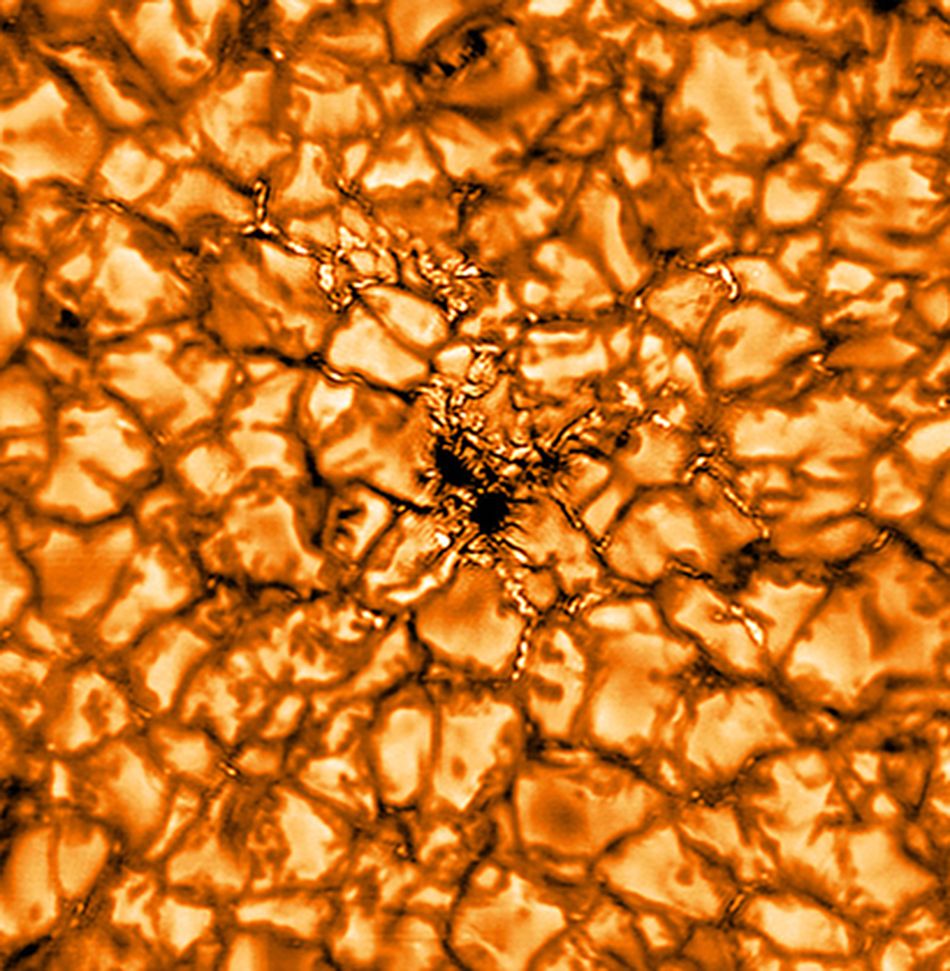

In a new photo release from the Leibniz Institute for Solar Physics, we get up-close views of the sun’s surface, which looks like an elaborate network of fiery land masses that are in fact solar magnetic fields shown at a very high resolution.

Image: KIS

Another photo shows us what a sunspot, which appears as a darker speck on the surface of the sun, looks like up close. Mashable’s weekend team firmly noted that this image exudes major “butthole vibes.”

Apologies to the entire science community, but hey, it’s true.

Image: kis

The images come from Europe’s largest solar telescope, GREGOR. They’re some of the first to surface following a major upgrade project that the telescope went through.

“This was a very exciting, but also extremely challenging project. In only one year we completely redesigned the optics, mechanics, and electronics to achieve the best possible image quality.” project lead Dr. Lucia Kleint said in the press release.

The team apparently saw a major breakthrough in March 2020 when the global pandemic left them “stranded” at the observatory. They used that time to “set up the optical laboratory from the ground up” but weren’t able to grab images of the sun due to winter snow storms.

“When Spain reopened in July,” the release continued, “the team immediately flew back and obtained the highest resolution images of the Sun ever taken by a European telescope.”

The images released in July, meanwhile, came from the Solar Orbiter. That one, a joint project between NASA and the European Space Agency, launched the telescope-equipped satellite into space on Feb. 9. The photos we saw in July come from its first “close” pass by the sun, at roughly 77 million kilometers from the star.

GREGOR’s images, meanwhile, were captured here on Earth by a very high-powered telescope. The level of detail evident in the images is incredibly impressive, but so too is the upgrading of the telescope itself. Especially in such a short period of time.

“The project was rather risky because such telescope upgrades usually take years, but the great team work and meticulous planning have led to this success,” Dr. Svetlana Berdyugina, director of the Leibniz Institute for Solar Physics, said in a statement. “Now we have a powerful instrument to solve puzzles on the Sun.”