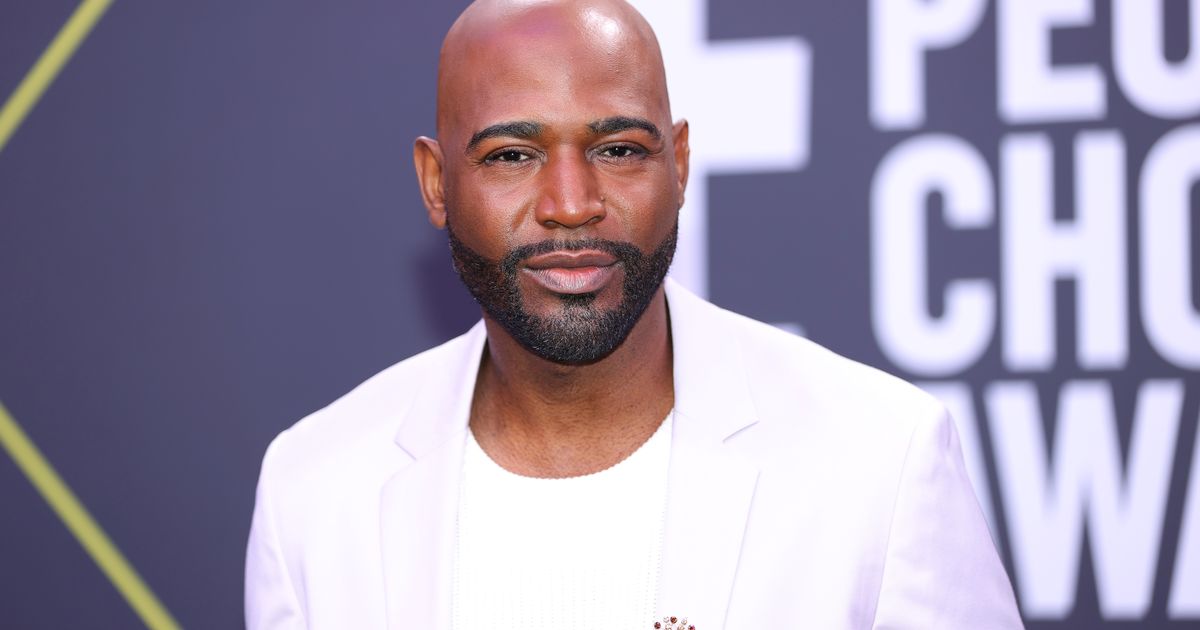

When Karamo Brown talks about mental health and wellness, he speaks with empathy and optimism. He can seamlessly pivot from darkness to light and back again while avoiding jargon that he must know from his professional experience in social work.

Brown’s ease, both with himself and those he counsels on Netflix‘s Queer Eye, is what makes him such an appealing messenger. Coaxing the show’s makeover subjects to better know themselves, he offers space for them to name their pain, whether it’s uncertainty, depression, anxiety, or grief. Brown helps them honor that before identifying the new habits essential to moving forward. He always seems to know what to do with suffering of all varieties.

So, as 2020 inches toward a tragic close, I decided to ask Brown how he handles pain that seemingly has no end. While widespread vaccination is within reach, the coronavirus pandemic has left millions hungry, on the verge of losing their homes, and without income. Republican Senator Mitch McConnell had reportedly been blocking a bipartisan relief bill that would help rescue Americans who, try as they may, can’t outmatch their intense stress and anxiety with meditation, better sleep, exercise, mindfulness, prayer, or any number of coping skills. They just need circumstances to change. They need a lifeline.

The advice Brown imparted during our Zoom call sounds a lot like using a coping skill, but it’s not one related to self-improvement, and it requires others to listen and respond.

When Brown first reaches a breaking point, he stops to thank himself.

“It’s very much like…thank you for trying and doing all you could do, because sometimes it’s all you can do,” he says. “I forgive myself for the things that maybe I thought that I should have been doing.”

“I forgive myself for the things that maybe I thought that I should have been doing.”

Brown knows this might sound “hokey,” but changing the narrative from negative to positive helps release overwhelming pressure born of stress and anxiety. That frees Brown from the blinders that make it harder to see the supportive people in his life to whom he can turn for help.

“I think that in those moments, something that I tell people is that it’s OK to say to people, ‘I need you to love me a little bit louder today.'”

In other words, Brown looks at the proverbial wall he’s hit and recognizes that it’s time to ask for help.

This may seem like an obvious strategy, but American politics, media, and culture are unpredictable when it comes to admitting such vulnerability. Some people are punished, told they deserve their misfortune. Others are viewed with sympathy, and help arrives swiftly. The wild swing from one direction to the next means too many people stay silent as they struggle.

Brown understands this well. As a teen, he began experiencing migraine, a neurological condition with multiple symptoms known for causing excruciating, long-lasting headaches. Some people don’t understand or take the disease seriously.

“When I had my migraine, I was like, if one more person tells me that this is just a headache and to take a pill, I was going to…I was going to explode,” he says.

Now, as a partner in the Know Migraine Mission, an initiative from the pharmaceutical companies Amgen and Novartis, he’s trying to lessen the stigma surrounding migraine.

Telling his friends and family that they need to “love me a little bit louder today” during moments of struggle — a remarkably candid declaration — didn’t come easily to Brown.

Eventually, he summoned the courage to tell loved ones they needed to educate themselves on the condition so they could support him. In general, he wants people to listen to the language they use with others. Jokes, veiled insults, gaslighting, and insensitive words in response to someone’s distress only make it harder for them.

“I think when you tell people in previous conversations that they were not worthy of help or what they were feeling was not right, it gives them the sort of idea that they can’t ask for help,” he says.

The fact that people are in such dire straits thanks to the pandemic that they’ve been forced to rely on people’s ability to be emotionally or financially generous — or hope the strained nonprofit safety net will catch them — is a catastrophic failure of leadership. And yet, here we are.

When our own government leaves people to suffer and die, only we can save each other. That means empowering ourselves to ask for help, learning how to insist that you deserve such kindness, no matter what you’ve been told before, and responding with compassion and whatever resources you can spare when a loved one, acquaintance, or stranger, sounds the call for aid.

This is what a breaking point can teach us. It need not be a solitary experience of panic and fear, where we feel ashamed of what we need and embarrassed that we can no longer cope. Instead, it can be a moment when a community can fulfill its purpose by listening, comforting, and delivering.

“We all need each other,” says Brown.

If you want to talk to someone or are experiencing suicidal thoughts, Crisis Text Line provides free, confidential support 24/7. Text CRISIS to 741741 to be connected to a crisis counselor. Contact the NAMI HelpLine at 1-800-950-NAMI, Monday through Friday from 10:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m. ET, or email info@nami.org. Here is a list of international resources.