Climate 101 is a Mashable series that answers provoking and salient questions about Earth’s warming climate.

During the historic Texas cold, people froze to death.

Even as the world warms, the potential for frigid Arctic air to plunge deep into to U.S. will continue to exist. Extreme cold in Texas during years like 1983, 1989, and 2011 foreshadowed the 2021 freeze, yet the state largely ignored a major 357-page report published in 2011, which urged a weatherization of Texas’ vulnerable energy infrastructure. That didn’t happen.

The freeze left us with tragedies and poignant icicle imagery. But such relatively rare, record-breaking cold extremes are occurring on a globe where winters, like all the seasons, are warming. In fact, in much of the U.S. winter is the fastest-warming season, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data compiled by Climate Central, an independent organization that researches climate change.

“A warming world is still one where we have many types of weather events. We’ll still have cold snaps,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and the director of climate and energy at the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental research center.

“We’ll still have cold snaps.”

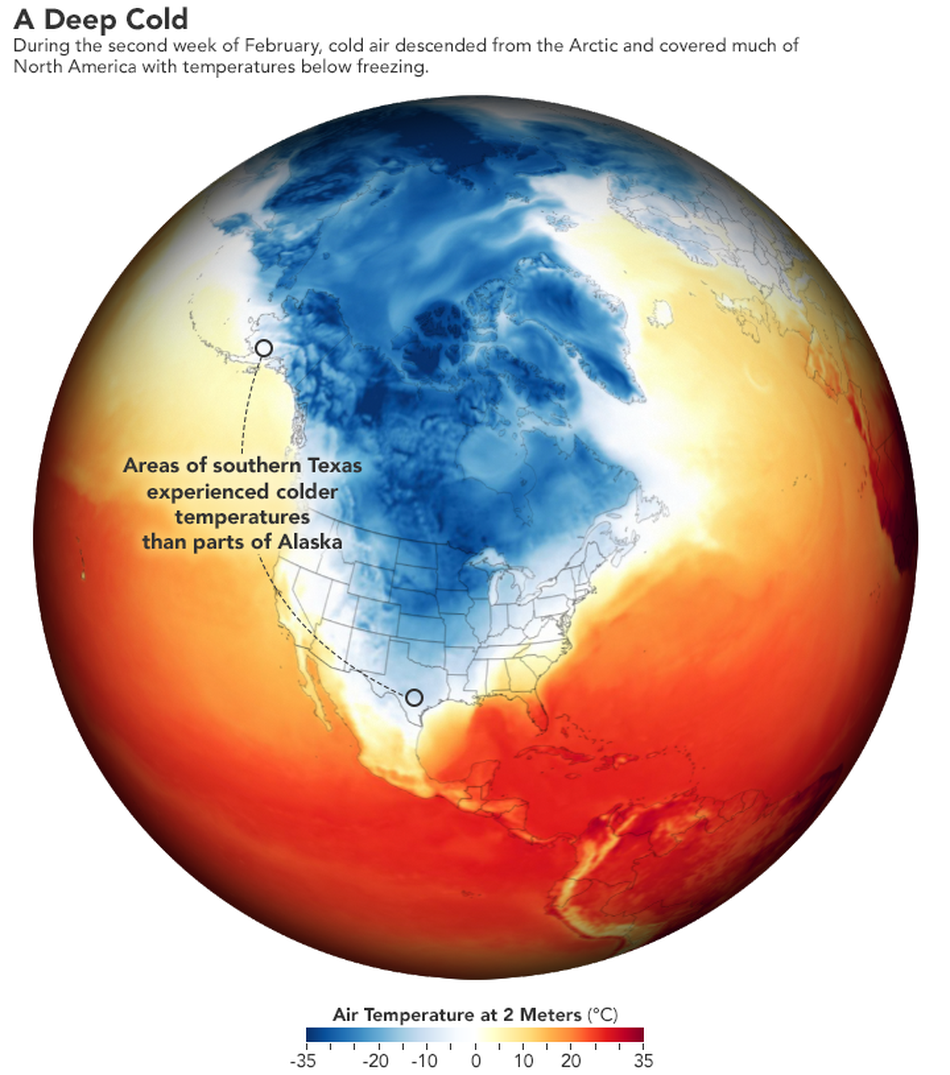

In Texas, winters are about three degrees Fahrenheit warmer than they were in the late 1800s, explained Hausfather. But during the recent freeze, temperatures plunged (in some places by almost 50 F below normal), shattering records in places like Fort Worth and Waco, while driving conditions to near historic lows in Houston. That’s because potent weather patterns allowed Arctic air to travel thousands of miles down into the U.S. Of note, the polar vortex — lofty winds that circulate atop the globe each winter — weakened this year, which played a big role in letting exceptionally frigid air spill south into the heart of the nation.

These sorts of events will inevitably happen again. Regardless of what the climate does, there’s going to be variable, dynamic weather moving through our profoundly chaotic atmosphere, explained Daniel Horton, a climate scientist at Northwestern University. During any winter, “there’s a chance it will be quite cold, and it will have major impacts on us,” said Horton. (Last winter, in contrast, was relatively wimpy for much of the U.S.)

So dramatic winter freezes will happen from time to time, even amid Earth’s accelerating heating trend, and as atmospheric scientists anticipate the coming years will be some of the warmest on record.

“You still have cold extremes even if the overall trend is more warming,” explained Isla Simpson, a researcher in the Climate and Global Dynamics Laboratory at the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Indeed, certain places in the U.S. may experience years of colder-than-average winter temperatures, even as the greater nation and world experiences warming. “It doesn’t mean locally you can’t have a place with several years in a row with an unusually cold winter,” said Simpson.

Cold air spills south in February 2021.

Image: nasa

U.S. winters are growing warmer.

Image: Climate Central

A question that looms large, however, is if climate change is making Arctic cold air surges more likely. It’s a hot area of research, but there is no high-confidence answer or nearly a scientific consensus. “It’s a very vibrant debate,” said Hausfather. “It’s an area of emerging science.”

Some research has suggested the possibility that as the Arctic rapidly warms, it can make weather extremes more likely: Specifically, the heating Arctic might make the jet stream (a band of powerful winds that separates cold Arctic air from warm southern air) more prone to meandering to the north or south, kind of like a loose, droopy rope. This could, for example, allow polar air to more easily swoop down from the Arctic. But other research hasn’t found such a link.

“Winter is not going away.”

Climate change, however, certainly isn’t a prerequisite for blasts of polar air. “We know that Arctic air can come down to Texas even without climate change,” said Hausfather.

But overall, expect warming winters. In our warming climate, the odds are weighted heavily in favor of daily high records breaking over low records by a rate of about two to one. These days, all-time high records trump all-time lows, too.

“The likelihood you’ll have record-breaking cold events is decreasing,” said Horton, of Northwestern University.

So which cold wave was more extreme? February 1899 or February 2021. The answer is …… not even close. February 1899 was much colder nearly everywhere. pic.twitter.com/QM01c1Y1cH

— Brian Brettschneider (@Climatologist49) February 18, 2021

The impacts of warmer winters are conspicuous, and mounting. Snowpack on Western mountains, which is integral for filling reservoirs, is declining. In some places, the lakes don’t freeze like they once did, meaning thin ice and depressed winter culture and activities. With thinner ice comes an increase in winter drownings. Milder winters mean insects that spread disease, like mosquitos, can hatch earlier and arrive in higher numbers.

Winter is changing. But like spring, summer, and fall, it will still arrive each year. And during some winters, Arctic air will bring rare, extreme weather.

“Winter is not going away,” said Horton.