Two high-profile cyberattacks on critical infrastructure companies over the past month have shone what experts say is a much-needed spotlight on the rising threat of ransomware.

An attack against Colonial Pipeline in May forced the company to temporarily shut down 5,500 miles of pipeline that it said supplies nearly 45 percent of the East Coast’s fuel. Colonial eventually paid the extortionists—a group known as DarkSide—nearly $5 million in Bitcoin. The FBI has since recovered roughly half of the ransom. Colonial confirmed the attack and thanked the FBI for its efforts in a statement.

Just weeks later, another ransomware attack, credited to the group REvil, struck JBS, the world’s largest meat supplier, forcing the company to close plants across the U.S. and Australia and pay approximately $11 million in ransom.

(The values of the ransoms referenced in this story have changed over the course of the media’s coverage of the incidents because they were paid in Bitcoin, a highly volatile cryptocurrency.)

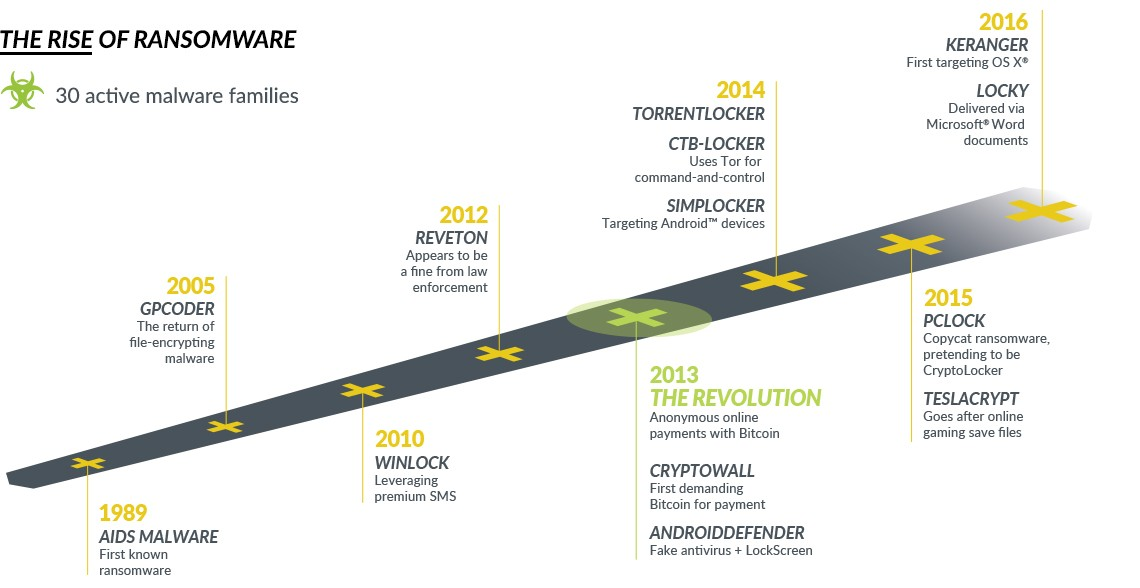

Ransomware is a type of malicious software, or malware, that encrypts files on a computer or network and holds them hostage until the owner pays the attacker the requested fee. It’s an old racket—what’s widely considered to be the first example of ransomware came in 1989, when malware was delivered via floppy discs to attendees at a World Health Organization AIDS conference.

So in some respects, the attacks against Colonial Pipeline and JBS are nothing new. Thousands of companies are targeted by ransomware each year, and many end up paying to recover their data. But cybersecurity researchers say these two attacks are indicative of how the ransomware threat is morphing—driven by a combination of economic factors and years of corporate secrecy and inaction.

“Americans, I think for the first time at the actual consumer level, saw the impact of these ransomware attacks,” said Adam Meyers, vice president of intelligence for cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike. “Organizations can’t stick their heads in the sand and hope this is going away. They need to invest and start taking this seriously.”

Is Ransomware on the Rise?

Certainly, the companies that make money from selling cybersecurity services report a rise in ransomware.

The cybersecurity firm SonicWall detected more than 304 million attempted ransomware attacks in 2020, a 62 percent increase over 2019. During the first five months of this year, the company tracked a 116 percent increase in ransomware attempts compared to the same period in 2020, and the 62.3 million attacks it detected this May were the most it has ever recorded in a single month, said Dmitriy Ayrapetov, vice president of platform architecture for SonicWall.

Most of those attacks are likely aimed at victims of opportunity—the perpetrator may send out waves of phishing emails at random hoping for just one or two victims to take the bait. But targeted attacks against corporations and government entities are also on the rise, Meyers and other cybersecurity researchers said.

CrowdStrike monitors organized criminal groups that are more intentional in selecting their targets, what the company calls “big game hunters.” In 2020, the firm recorded at least 1,377 big game hunter infections. So far in 2021, CrowdStrike has recorded 1,024 such attacks, Meyers said, with an average ransom demand of $5.6 million.

But it’s hard to truly quantify the number of attacks, the type of targets, and the damage done. There’s no comprehensive data source for ransomware attacks. The data we do have is either self-reported (and many companies and individuals don’t report) or comes from cybersecurity firms that profit by selling protections against attacks and are therefore keen to publish reports demonstrating the severity of the situation.

The FBI requests that organizations affected by ransomware report incidents so that the agency can better piece together trends. The agency’s numbers actually show a decline in incidents but a rapid rise in damages. In 2016, there were 2,673 self-reported incidents resulting in $2.4 million in adjusted losses, according to the FBI’s annual data. That dropped to 1,783 incidents causing $2.3 million in losses in 2017, then 1,493 incidents causing $3.6 million in losses in 2018. In 2019, there were 2,047 reported incidents and $8.9 million in losses, and in 2020 the FBI recorded 2,474 incidents and $29.1 million in losses.

The FBI’s numbers are almost certainly vast undercounts because many businesses decide not to publicly disclose successful ransomware attacks in order to protect their reputations with shareholders and customers.

Why Is Ransomware on the Rise?

The pandemic certainly increased many organizations’ vulnerability to ransomware, experts said. Especially during the early days of work from home, when many employees were forced to use their own equipment, company and government systems were being accessed on personal computers that were also used for any number of other potentially risky activities, from playing online games to surfing the web.

The rising value of Bitcoin, cyber criminals’ preferred form of payment, over the last year has also added to the attractiveness of ransomware.

But there are two changes within the ransomware industry—because that’s what it is now—that experts say have been driving the increase in attacks since before the pandemic.

“One of the causes of the recent increases we’re seeing in ransomware is that they’ve pivoted,” said Darren Shou, the chief technology officer for NortonLifeLock. “Instead of just being a threat where they lock down access to your data, now there’s a dual-threat where if you don’t pay that ransom they threaten to release your data.”

The Babuk ransomware group recently targeted Washington, D.C.’s Metropolitan Police Department with this type of attack. After the department declined to pay the requested $4 million ransom (it did allegedly offer to pay $100,000), the group published hundreds of embarrassing pages from MPD officers’ background investigations. The added threat of embarrassment and liability from having sensitive data published increases the potential financial pain for victims, making them more likely to pay ransoms. The more ransoms get paid, the more likely ransomware attacks become.

The second major change is the emergence of “ransomware as a service,” or RaaS. In addition to launching their own attacks, the most sophisticated ransomware groups are increasingly offering to sell their tools to aspiring criminals as a bundle, providing not just the malware but also the phishing operation, payment platform, and premade data leak site.

The Colonial Pipeline attack perpetrated by DarkSide appears to have been an RaaS operation. Following the immediate flurry of news about the pipeline’s shutdown, which brought unwanted attention to the group, DarkSide published a statement on its website (on the dark web) saying “from today we introduce moderation and check each company that our partners want to encrypt to avoid social consequences in the future.”

“[RaaS] really lowers the barrier of entry into this business,” Ayrapetov said. “It’s a natural kind of evolution of a business model, and you get more scale that way. As this scales, there are more players who might be more reckless.”

What Can Be Done?

Cybersecurity experts say the solutions are widely known—they’re just not widely implemented.

Organizations need to educate their employees about phishing and social engineering attacks, but there are also some technical and infrastructure changes that can make a big difference, experts said.

Not everyone needs to have administrator access to their own computer, and organizations should segment their networks to ensure employees can only access the parts they need for their jobs.

On top of that, companies should maintain air-gapped copies of their data—regularly updated backups that aren’t connected to the network and are therefore immune to ransomware encryption. They should also be using multifactor authentication and ensuring that they’re implementing software patches as soon as the patches are released.

Some of the economic factors spurring ransomware fears—including the insurance industry that profits from them—have also led to more controversial proposals.

The Government Accountability Office reported that the percentage of companies paying for cyber insurance nearly doubled from 2016 to 2020. And as attacks and ransom demands increased, the premiums for those plans went up by as much as 30 percent between 2017 and 2020, while the amount those insurers promised to cover in damages for some sectors went down.

Adam Wandt, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice who researches cybercrime, said the security blanket of cyber insurance has convinced some organizations they don’t need to implement the human and technical changes necessary to stop ransomware attacks, and that the only real long-term answer is for governments to pass laws banning organizations from paying ransoms for certain kinds of data.

The FBI already urges organizations not to pay, but in some cases not paying means going out of business.

“Ransoms should never be paid and those that do should understand the damage they’re causing to our society for their own benefit and gain,” Wandt said, acknowledging that such laws could initially be devastating to victims. “Paying the ransom will lead to nothing more than more attacks on our critical infrastructure.”

This article by Todd Feathers was originally published on The Markup and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.