A huge virtual gallery of museum skeletons is fully open for viewing. A large group of scientists has painstakingly created 3D reconstructions of thousands of vertebrate specimens, which are now freely available to view online. The endeavor not only allows the public to see once-inaccessible museum collections, but it is already improving scientific knowledge.

Advertisement

The project is called openVertebrate, or oVert, and has been years in the making. Since 2017, scientists from 18 museums, universities, and other institutions around the U.S. have banded together to catalog the vast number of vertebrate specimens in their possession, most of which have been stored away from the public eye. The project is led by David Blackburn and Edward Stanley, scientists at the University of Florida and the Florida Museum of Natural History. The team’s summary of the project is now published in the journal BioScience.

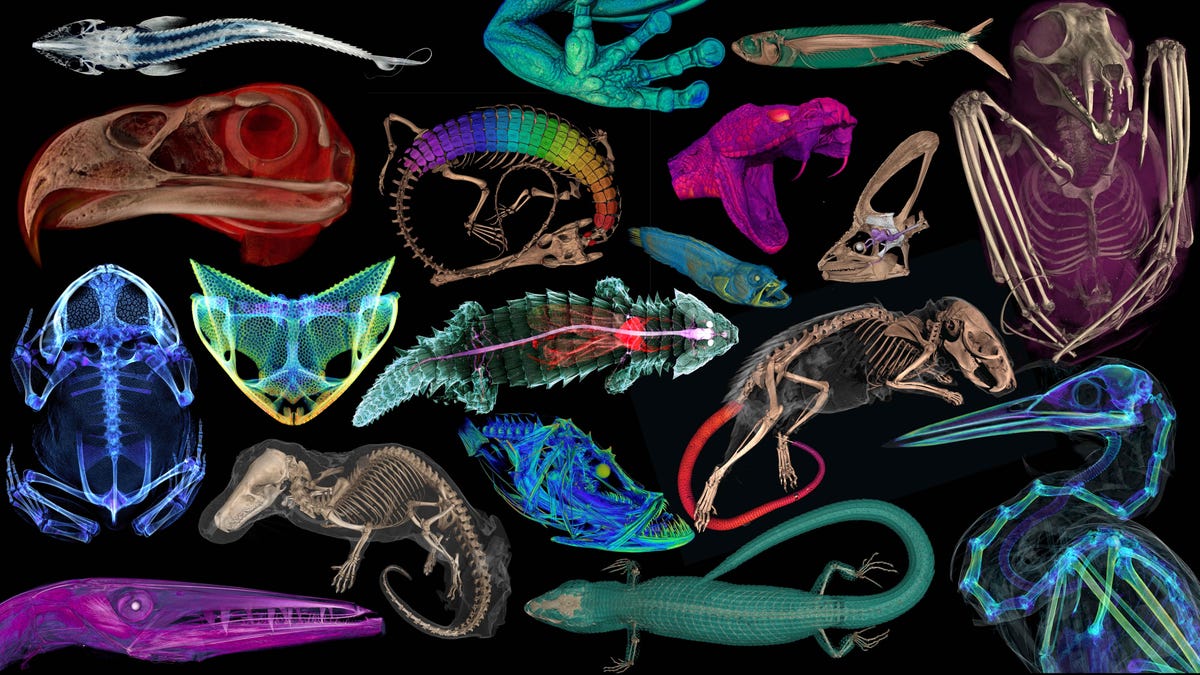

More than 13,000 specimens have been cataloged, representing a wide range of vertebrate species from different branches of life, including amphibians, fish, reptiles, and mammals. The researchers ran CT scans of the specimens and used them to produce accurate 3D images.

“The CT scans use X-rays to create a three-dimensional view inside these specimens, allowing us to visualize the internal anatomy of these animals in incredibly high detail and in ways we could not before,” Edward Stanley, an associate scientist at the Florida Museum of Natural History, told Gizmodo in an email.

For some specimens, they also used temporary contrast-enhancing stains to better outline soft tissues like skin and muscles. And in one particular case, for a humpback whale too big to be scanned normally, the researchers took apart the whale’s skeleton, methodically scanned each bone, then put the skeleton back together both physically and digitally.

“Though some vertebrate species are very familiar to the public and to scientists, there are many more for which we know exceedingly little about their lives. These 3D datasets provide the first windows in the biology of some poorly known species,” David Blackburn, the curator of herpetology at the Florida Museum, told Gizmodo.

Some of the team members have already made discoveries as a result. While scanning African spiny mice, Stanley found out that these rodents had bone-plated structures covering their tails—a feature common to reptiles and fishes but not typically found in mammals, with the exception of armadillos. His team’s work confirming the find was published last May.

Though there are many other lines of research now possible with oVert, the team is also heartened by the new opportunities for public outreach and other unexpected uses that their project has and will further enable.

“We have many artists from around the world using these 3D datasets as either inspiration or actually incorporated into their digital or physical art,” said Blackburn. “We’ve heard from veterinarians using these data to plan surgeries, as well as enthusiastic members of the public that are simply crazy for skulls and are 3D-printing skulls for their enjoyment at home.”

Added Stanley: “The most exciting aspect of this project, for me, is the increased variety of uses and users of natural history collections. While we expected these data would appeal to researchers, it was really gratifying to see so much engagement from educators, students, artists, animators, and people who were simply interested in anatomy and the diversity of life.”

Here are some of the many, many specimens now digitally preserved by the oVert project.

Services Marketplace – Listings, Bookings & Reviews