While studying Europa’s magnetic field in 2000, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft inadvertently collected evidence of watery plumes shooting out from the moon’s icy surface, according to new research.

Advertisement

It’s becoming increasingly clear that Jupiter’s moon Europa is bursting at the seams and actively shooting plumes of watery vapor into space. New research published in Geophysical Research Letters is bolstering this claim with some rather unusual evidence: protons—or rather, the lack thereof.

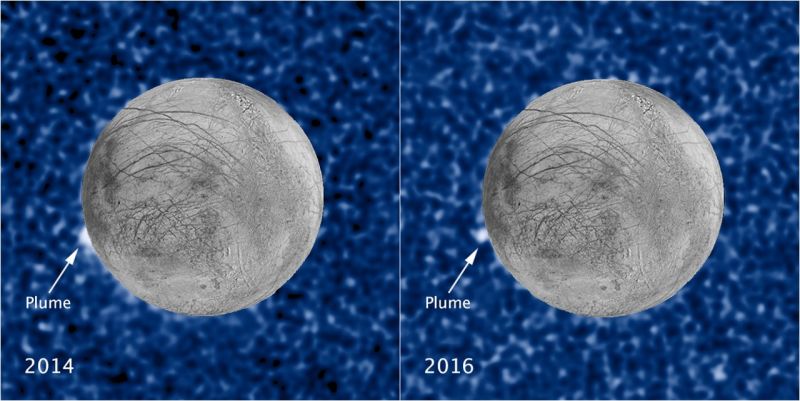

Europa is covered in a thick layer of ice, which scientists strongly suspect is hiding a subsurface ocean. Steady gravitational tugs from Jupiter keep this water warm and liquid, but scientists have good reason to believe that some of this water escapes by bursting through cracks on Europa’s icy surface. Evidence of this was first detected by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2013 and again in 2014 and 2016.

A similar phenomenon was spotted by NASA’s Cassini orbiter in 2008, when it detected evidence of water plumes shooting out from Saturn’s icy moon Enceladus, which also appears to host a subsurface ocean.

Back in 2000, NASA’s Galileo spacecraft performed a flyby of Europa, in an effort to study the moon’s magnetic field. As it did so, the probe was on the look-out for protons, subatomic particles carrying a positive charge.

“Galileo had an instrument on board—the Energetic Particle Detector—specifically designed to detect such super-fast charged particles and study them,” Hans Huybrighs, a research fellow at the European Space Agency and the lead author of the new study, told Gizmodo. “The scientists who designed this instrument wanted to characterize these particles, figure out how they become accelerated, and also how they interact with the moons of Jupiter.”

Advertisement

Europa is bombarded by these fast charged particles, but detecting water plumes was hardly the goal during Galileo’s flyby. Space science is “full of these kind of fortuitous discoveries,” said Huybrighs.

Protons should’ve been recorded in abundance, but Galileo, while zipping over the moon’s northern polar regions, barely detected any. Scientists initially attributed the dearth of protons to Europa itself, figuring that the moon blocked Galileo’s proton detector.

Advertisement

The new study revisited the spacecraft’s 20-year-old data, resulting in a very different conclusion. To better understand why Galileo might have encountered so few protons during its flyby, the researchers used models to simulate the motion of these subatomic particles around the moon.

Advertisement

A drop in protons was observed when the particles lost their electrical charge in the moon’s atmosphere. The authors note that a presumed plume of water vapor, in addition to interfering with Europa’s thin atmosphere, also disrupted magnetic fields in areas scanned by the spacecraft.

“Basically, when the fast protons collide with uncharged particles from the plume, the uncharged particles ‘steal’ electrons from the protons,” Huybrighs told Gizmodo. “The protons then become uncharged particles themselves. The fast protons are trapped in Jupiter’s magnetic field, but when they lose their electrical charge, they are no longer trapped, but they are still very fast. At that point they escape the ‘shackles’ of the magnetic field very fast and we see a decrease of the fast protons as a consequence.”

Advertisement

The researchers explored various causes of proton disappearances, but it was only when plumes were added to the simulations that they were able to reproduce what they saw in the data. Looking ahead, Huybrighs said he will keep investigating Galileo data in hopes of finding more about Europa and other Jovian moons.

This is an exciting result, as it’s further evidence of subsurface water pouring out into space and onto Europa’s surface. Astrobiologists suspect that both Europa and Enceladus may have the right stuff for life, making these moons ideal targets for future scientific missions.

Advertisement

The good news is that the ESA has an upcoming mission, called JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer), which will send a probe to the Jovian system. JUICE is scheduled to launch in 2022 and arrive at Jupiter in 2029, where it will study Europa and its suspected plumes, as well as Ganymede and Callisto, two other giant Jovian moons. Huybrighs is currently investigating ways to detect these plumes once the JUICE mission begins.

Advertisement

“JUICE will carry the equipment needed to directly sample particles within the moon’s water vapor plumes and also to detect them remotely,” he said. “Maybe we could thereby reveal the secrets of Europa’s vast, mysterious, and potentially habitable subsurface ocean.

NASA is also working on mission, called the Europa Clipper, which could launch as early as 2023.

Advertisement