Many nocturnal animal species use light from the moon and stars to migrate at night in search of food, shelter, or mates. But in our recent study, we uncovered how artificial light is disrupting these nightly migrations.

Electric lighting is transforming our world. Around 80% of the global population now lives in places where night skies are polluted with artificial light. A third of humanity can no longer see the Milky Way – the galaxy our solar system belongs to. But the light at night has deeper effects. In humans, nocturnal light pollution has been linked to sleep disorders, depression, obesity, and even some types of cancer.

Studies have shown that nocturnal animals modify their behavior even with slight changes in night time light levels. Dung beetles become disoriented when navigating landscapes if light pollution prevents them from seeing the stars. Light can also change how species interact with each other. Insects such as moths are more vulnerable to being eaten by bats when light reduces how effective they are at evading predators.

Relatively little is known about how marine and coastal creatures cope. Clownfish exposed to light pollution fail to reproduce properly, as they need darkness for their eggs to hatch. Other fish stay active at night when there’s too much light, emerging quicker from their hiding places during the day and increasing their exposure to predators. These effects have been observed under direct artificial light from coastal homes, promenades, boats, and harbors, which might suggest the effects of light pollution on nocturnal ocean life are quite limited.

[Read: This startup is fighting air pollution with AI]

Except, when light from street lamps is emitted upwards, it’s scattered in the atmosphere and reflected back to the ground. Anyone out in the countryside at night will notice this effect as a glow in the sky above a distant city or town. This form of light pollution is known as artificial skyglow, and it’s about 100 times dimmer than that from direct lighting, but it is much more widespread. It’s currently detectable above a quarter of the world’s coastline, from where it can extend hundreds of kilometers out to sea.

Humans aren’t well adapted to seeing at night, which might make the effects of skyglow seem negligible. But many marine and coastal organisms are highly sensitive to low light. Skyglow could be changing the way they perceive the night sky, and ultimately affecting their lives.

Crustaceans in the spotlight

We tested this idea using the tiny sand hopper (Talitrus saltator), a coastal crustacean that is known to use the moon to guide its nightly foraging trips. Less than one inch long, sandhoppers are commonly found across Europe’s sandy beaches and named for their ability to jump several inches in the air.

They bury in the sand during the day and emerge to feed on rotting seaweed at night. They play an important role in their ecosystem by breaking down and recycling nutrients from stranded algae. If you turn over washed-up seaweed on an evening beach walk, you should have no trouble finding them.

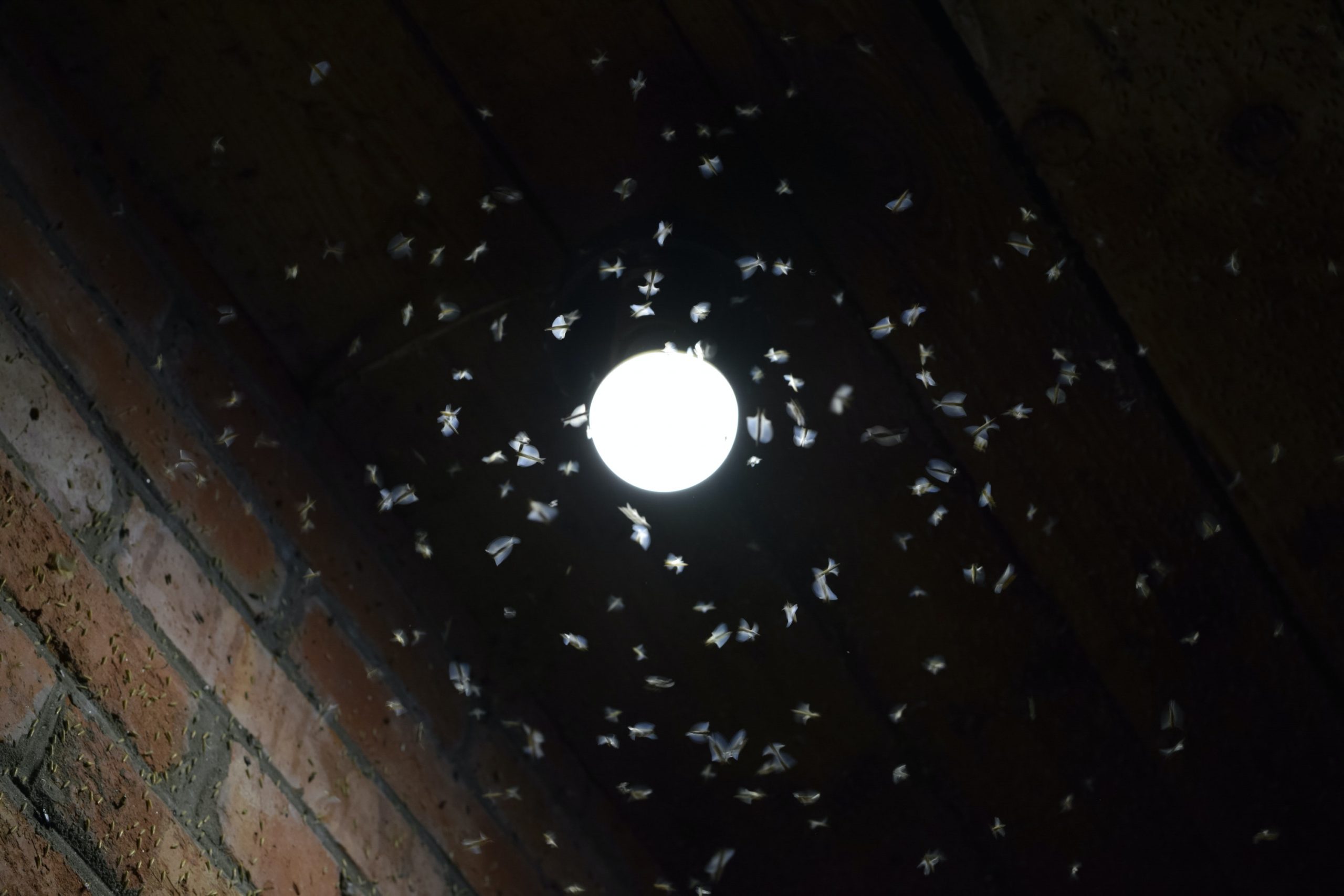

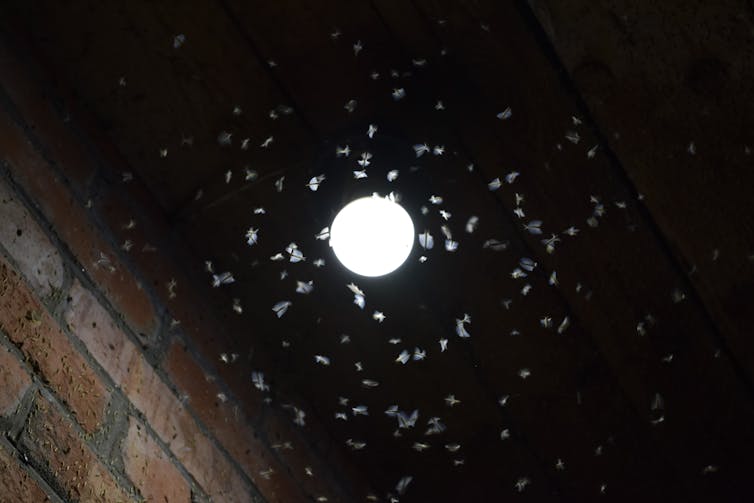

In our study, we recreated the effects of artificial skyglow using a white LED light in a diffusing sphere that threw an even and dim layer of light over a beach across 19 nights between June and September 2019. During clear nights with a full moon, sand hoppers would naturally migrate towards the shore where they would encounter seaweed. Under our artificial skyglow, their movement was much more random.

They migrated less often, missing out on feeding opportunities which, due to their role as recyclers, could have wider effects on the ecosystem.

Artificial skyglow changes the way sandhoppers use the moon to navigate. But since using the moon and stars as a compass is a common trait among a diverse range of sea and land animals, including seals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and insects, many more organisms are likely to be vulnerable to skyglow. And there’s evidence that the Earth at night is getting brighter. From 2012 to 2016, scientists found that Earth’s artificially lit outdoor areas increased by 2.2% each year.

As researchers, we aim to unravel how light pollution is affecting coastal and marine ecosystems, by focusing on how it affects the development of different animals, interactions between species and even the effects at a molecular level. Only by understanding if, when, and how light pollution affects nocturnal life can we find ways to mitigate the impact.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Svenja Tidau, Postdoctoral Researcher in Marine Biology, Plymouth University; Daniela Torres Diaz, PhD Candidate in Biology, Aberystwyth University, and Stuart Jenkins, Professor of Marine Ecology, Bangor University under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Pssst, hey you!

Do you want to get the sassiest daily tech newsletter every day, in your inbox, for FREE? Of course you do: sign up for Big Spam here.