November 2020 had something in common with January 2020, May 2020, and September 2020.

Globally, they were all the warmest respective months in the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service records, which maintains a data set going back to 1979. (In fact, all the months so far this year were some of the warmest such months ever recorded). The Copernicus data is one of many global temperature records, which are in impressive agreement, showing Earth’s accelerating rise in surface temperatures. Other records, like NASA’s, go back to the 1880s.

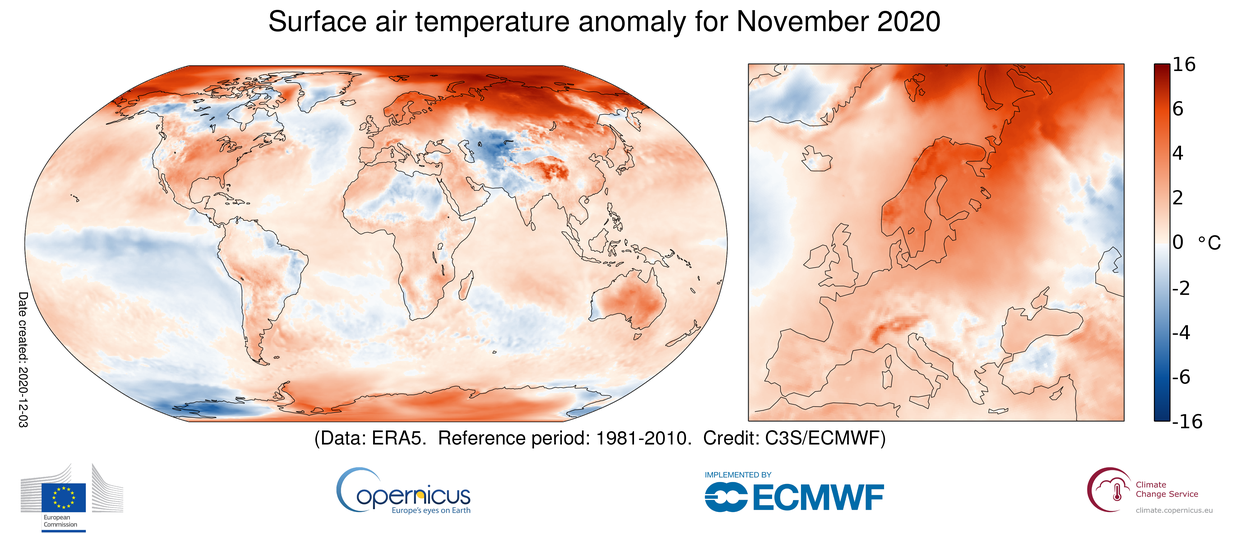

The Copernicus Climate Change Service reported on Monday that November was the warmest by a “clear margin.” Overall, the autumn month was nearly 0.8 degrees Celsius, or some 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit, warmer than the 1981-2010 average. It beat the previous warmest Novembers (in 2016 and 2019) by over 0.1 C, which is quite a margin for global temperatures, as they encompass weather observations averaged from all over the planet.

“It’s a clear sign the world is warming when you keep setting new records,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist and the director of climate and energy at the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental research center. Hausfather had no role in the Copernicus temperature report.

Global surface temperatures compared to the average (red shades are warmer than average).

Image: COPERNICUS CLIMATE CHANGE SERVICE / ECMWF

ERA5 global temperature anomaly for 1-25 November easily exceeds the previous record set in Nov 2016.

We’ve very likely just lived through the warmest November on record. And what’s notable, during moderate La Niña. pic.twitter.com/GM0pP5Xhp8

— Mika Rantanen (@mikarantane) November 30, 2020

The repeatedly warm months in 2020 are all the more impressive, noted Hausfather, due to the presence of a natural weather pattern called La Niña. During La Niña, a large swath of the surface waters in the equatorial Pacific Ocean cool, as cold waters rise to the surface. This has an overall planetary cooling effect. But still, today’s human warming impact is enough to overwhelm this trend.

“It’s all the more remarkable because it’s happening on the backdrop of a moderately strong La Niña event,” said Hausfather.

In November, temperatures across most of the Arctic, northern Europe, and Siberia were much warmer than average. It was also warmer than usual over much of the U.S., Australia, and large parts of South America and Africa.

The planet is reacting to the highest atmospheric levels of heat-trapping carbon dioxide in at least 800,000 years, but more likely millions of years. Yes, both CO2 levels in the atmosphere and global temperatures fluctuate naturally, but what’s happening now isn’t natural. After past ice ages, the planet hasn’t warmed nearly this fast. As NASA notes, based on past climate records (such as from deep ice cores or tree rings):

“This ancient, or paleoclimate, evidence reveals that current warming is occurring roughly ten times faster than the average rate of ice-age-recovery warming. Carbon dioxide from human activity is increasing more than 250 times faster than it did from natural sources after the last Ice Age.”

The consequences of this warming are many:

The Copernicus Climate Change Service reports the warming from January through November is on par with 2016, the warmest year on record. This means 2020 will likely end up being one of the warmest years on record, if not the warmest. Importantly, humanity still has great sway over the climate system, and can still curb carbon emissions to avoid the ever-worsening consequences of a heating planet.

For now, however, the records keep breaking.

“These records are consistent with the long-term warming trend of the global climate,” Carlo Buontempo, director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, said in a statement. “All policy-makers who prioritize mitigating climate risks should see these records as alarm bells and consider more seriously than ever how to best comply with the international commitments set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement.”